That slow rise to mediocrity

December 26, 2022, 8:23 am , by Richard Lutz

The newshound with the dyed red hair, the gentle Mr Sweet, the politician and his white loafers…RICHARD LUTZ remembers his early days in journalism

*************

I was outside the family home of Liverpool footballer Alan Hansen in the small mining village of Sauchie. It was a Scottish spring, many decades ago.

Soon after signing a £100,000 contract with the team, young Alan had got himself into a spot of what a magistrate called “ungallant behaviour” on Blackpool beach. The papers were interested. My job was to find out how his family would react – a common job in any journalist’s life.

“How do you feel about…?” And then wait for a slamming door, a mouthful of bile or, sometimes, a pleasant chat and cup of tea.

I knocked. A door opened and Hansen’s father filled the frame. There was a pause. Mr Hansen was in shorts. Muscles rippled through an upper torso. An arsenal of weights studded the living room. He was fit. And he knew pretty well why I was there.

That pause. You never know what will happen – especially when a protective parent is approached. He gave me an up and down and then broke into a wan smile, invited me in and gave me a paternal interview. And that cup of tea. But he didn’t let me touch his barbells.

My life and times at the Alloa Advertiser and Journal- The ‘Tizer – my first newspaper job in Britain and one that bleached out the rough bits before I moved on.

A year before, I was on a building site mixing cement. Jack Hardy, the owner of the Advertiser, had taken a chance on me and I had happily exchanged shovel for shorthand.

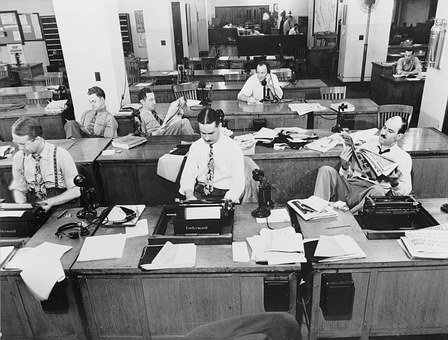

For a glorious £48 per week (more than as a brickie’s mate, I tell you confidentially), I was shown the windowless reporters’ room with its rattly metal desks and bad lighting; made to sit in night class for my Pittman’s shorthand along with apprentice secretaries hoping to get up to the 100 words per minute minimum; and, had rammed into my brain Scots law, council procedure and the grammar and rhythm of British journalism. ‘Tight, keep it tight’ was the rule. Keep it tight on The ‘Tizer.

After banging on the portals of Pulitzer Prize journalism with my first story about an old woman who was knocked off her bicycle, I soon clocked that every reporter needs a patch. Or else it was going to be a long life of grannies injured on the way to the shops. I needed a stake in something. I needed a beat, a corner to spread wings. It became a prime goal.

But there was little room at the top of that airless newsroom. Gordon Gillies, our ’chief reporter’, was an Alloa lad and knew everyone. He was a perpetual motion machine for Yon Tizer who gobbled up all the reasonable stories and hammered them out. He had a triple lock on the front page- he’d whiz into the composing room and breathlessly help lay out the splash with his exclusive. He was a whirlwind, was Gordon. He ate stories for breakfast, headlines for lunch, vital tip-offs for high tea and dinner. He didn’t smoke or drink. He was too busy.

I looked around to see what Mr Hardy wanted. With his long sideburns, his stooping body, his long spindly fingers and his steel-rimmed specs, he was a Dickensian figure. It wasn’t hard to imagine that tucked behind his battered roll-top desk were his ear trumpet, his spittoon, his chamberpot.

He was Old School. And especially keen on the particulars. Once he was spotted kneeling on the floor of the newspaper’s shop sticking price labels on individual ballpoint pens. He liked a sharp ship, did Mr Hardy. As for the reportage? News? Exclusives? Sport? ‘What makes money is second-hand car ads’ he bluntly told a muted newsroom one morning. It took the wind out of our reporting sails for a week. I expected Bob Cratchit to walk through the door at any moment armed with quill and inky fingers.

It was said Boss Hardy used to run a publishing company in West Africa before somehow decamping to the ownership of the Alloa Advertiser and Journal in the heartlands of Clackmannanshire, a tiny county, The Wee County in fact, cuddled between posh old Stirlingshire and the grand sounding Kingdom of Fife.

I wanted to find out what Africa Jack fancied, needed, could not do without. But Mr Hardy’s interest in professional advancement and upskilling was soon obvious. I approached him and he continued pricing up his precious pen collection, didn’t so much as turn around and re-directed me with a boney finger to the newspaper’s editor, Lawrence Sweet.

Mr Sweet ran the paper in erratic form, stoked by a bellyful of anxiety. He was a walking coil of nervous twitchiness, chainsmoking Players Number 6 until his stumped fingers turned a brutal brown. His shoulders moulded into a continual slump and the cuffs of his baggy jacket drooped over raw knuckles. He was petrified of Hardy, frightened perhaps that his boss would lean back, grab that old ear trumpet and lamp him one on the head over that error strewn page three article covering the Coalsnaughton Flower Show.

Mr Sweet was also frightened of the thrusting Gordon, of Jennifer the sharp reporter with a university education, of old Mr Murray in the corner with tattered tales of newspaper glory days and, of course, scared rigid of ‘Our Readers’ who would intermittently invade our shabby offices, loom over the misshapen metal desks and fiercely fire off a fusillade of unjustified complaints and unqualified demands which Mr Sweet would quickly accept as they plundered the petty cash box, sold the linotype machine for scrap, nicked all the McVities biscuits, busily pocketed the reduced pens and filed class action suits against Boss Hardy (note: this last paragraph is utter rubbish- ‘Tizer readers were kind and courteous).

Gentle Mr Sweet turned especially stiff with terror when our dapper and ambitious MP, George Reid, made his fortnightly entrance. The young elfin-sized politician intrigued us all, especially when he turned to Russian and bursts of Bulgarian to carry out sensitive phone calls. In the gloom of our newsroom, he was a cosmopolitan demi-god descending from the heady heights of Westminster to bless us with his Parliamentary sophistication.

George had a free hand with his weekly columns in the ‘Tizer. He knew which end of a typewriter was up; he’d been on Fleet Street and the authoritive TV investigative show World In Action. It was even rumoured he had ‘a computer’ in his constituency office. One day Mr Sweet announced that the MP’s weekly column, elegantly called Quid Pro Quo, would be re named Tit for Tat.

He had the temerity to ask the MP the reason. Lawrence explained the exchange: “George told me: ‘Lawrence, this is Alloa, not Edinburgh .’ ‘’

And then what happened? asked fellow reporter Mike Watts, who sorely wanted to leave weekly journalism and start a new life in leisure footwear.

Lawrence sighed: ‘Bloody Nora..’. The oath hung in the air like damp washing. “Mr Reid didnae half stairt blurting Russian into that wee phone over there.”

The column’s banner changed that afternoon. It was the first and last time that I have ever seen a contributor, whether a man off the street or an MP, tell an editor what to print, how to headline it or how to produce it. To say the least, the rest of MP George’s copy was never touched. But then again, it was pretty good anyway.

I met Mr Reid 20 years later in another life when I was at an editorial conference representing an English tv station. “I kinda thought you’d leave Scotland and head south,” he said slowly, worldly, knowingly. “Everyone does…”

The short sharp lesson….

I tried courts for a while with their arcane Scots procedures. Judges were sheriffs, prosecutors were procurator fiscals and a case could be ‘not proven’ -my guess was in trials when a defendant couldn’t be found guilty but the court damn well knew he was. I continually heard the summing up by Sheriff Henderson when he laid down the law to an unemployed miner from Tullibody (no fixed abode) who had gone on a week end rampage: “You need a short sharp lesson, Johnstone.” he would intone as he scratched his wig, re-read damning social enquiry reports and sent the looting, pillaging drunken rampager to a six week holiday at The Bar L… the boiled down nickname for Glasgow’s notorious Barlinnie Prison.

“Short sharp lesson.” I quickly learned how to scratch that phrase into shorthand real fast. Sheriff Henderson used it daily. But my copy was still all over the place; my shorthand, which had to be accurate, even shakier.

I soon realised that most of the reporters ran a mile when local councils were mentioned. But I felt that this was where potentially good stories were cooking. Plus you were nestled down in a centrally heated building, had access to a moderately comfy press room and could grab a passable cup of coffee. But, unfortunately, this was offset by the deadening meetings, mind-numbing, tedious, meandering and peopled with tiresome county politicians and po-faced officials. Quickly, I found out that gems lay a-bubbling underneath.

I decided to call this patch my own. Gordon thought I was mad. Jennifer was happy to never attend another dreary session. Mr Hardy couldn’t care less, re-labelling price tags was probably more his scene. Mr Sweet was, I think, glad to get me out of the office and out of the courts before we were all hung drawn and quartered outside Alloa Town Hall. ‘Jings,’ he proferred in an exotic Clackmannanshire patois, ‘I ken you’ll dae gie weill, son..’ or something to that effect which I never fully understood. And still don’t. ‘Nae fancy stuff noo. Just the wee facts. The council facts, son.’ And he’d haul in another funnel of Number Six smoke down his throat and scratch a knuckle permanently raw with anxiety.

Well, soon the ‘wee facts’ became huge facts. Colin Liddell from the Edinburgh Evening News and Tom Crainie, a relentless freelance, made a habit of patrolling local authority corridors after the dreary meetings to unpeel story after story. They were especially adept at discovering exactly which dregs of dirty business were discussed ‘in camera’ after the press was chucked out. They were great reporters. They soon found out that the cosmopolitan officials at the regional council had led elected members up the garden path and into rubber stamping cheap mortgages for the council’s chief management. Instead of 10% annual interest, they’d be offered 5% deals. And the taxpayer would foot the difference.

Colin and Tom pump-primed an Alloa councillor -a delightfully friendly ex-miner called Sam Ovens- and the tale quickly became the ‘half price mortgage scandal’. The story went ballistic. Glasgow and London papers salivated and Sam would not leave it alone. His own ruling Labour Party was furious that he was questioning their dubious decision; senior officials had their in-house lawyers confirm it was all above board. The chief executive, himself a beneficiary of the cheap deal, was mad as a haggis in a jam jar. And the press banged on and on about it as Harold Wilson’s Westminster government tottered.

I used to visit Cllr Ovens in his council house: a chat, a small interview, scraps of hints and clues. He truly believed in open government in this little closed world of Clackmannanshire. It was simply wrong that some people, he felt, got special deals in life while others barely made ends meet. He was fast falling out of Labour’s favour.

I especially liked it when Sam’s young twin daughters would sit next to him during my visits and he’d ask if I wanted another cup of tea. ‘The Twinnies will get it for you.’ he would say. And off The Twinnies would go to the small kitchen to make The Man from The ‘Tizer another cup. And another biscuit. I never found out the girls’ real names. Fiona and Sue? Marie and Wendy? In time, Sam called it quits and took to the cloth and the church.

All through this story, Mr Sweet could not see why Clackmannanshire, The Wee County, would be interested in this hifalutin’ mortgage story. I reminded him that Cllr Ovens represented a local ward (and readers). He let my copy flow on that simple note.

Well, the surprisingly supine councillors approved the dubious deal and the media frenzy carried on. I moved on and came up with story after story that was off the agenda. But that mortgage scandal was a a grim shadow stalemating all other activity. It really was the only tale in town.

This was especially galling for the Labour boss, a tough old pol called Joe Gilmour. He was a big bellied hard man who wore well-made suits, smoked incessantly, ruled the roost with a tight fist and, I can’t forget this, wore white loafers with gold tassels. He looked as if he’d be more at home on a yacht moored in a Florida marina, swilling quality bourbon aided by a bevy of Miami Beach beauties – not piling through braineating council minutes about roads, revenue budgets, school fencing and rubbish bins. But maybe I was wrong. Maybe Cllr Gilmour, with his gold tassels, read stories to disabled orphans on Christmas Eve or raised rare Nepalese orchids in his tiny greenhouse or was a champion cross channel swimmer. Or maybe not.

But he did look hard, talked hard, acted really hard. His whole body seemed architected to stolidly stand guard at the end of a bar. He treated reporters with sublime disdain. If he acknowledged our rumpled appearance at all.

It was he who one day took a note while in the debating chamber, Rothmans in hand, and actually broke a cold horrible sliver of a smile. He handed it to a lower form of Labour councillor and nodded. The note came to the press desk. Prime Minister Wilson had quit.

Cllr Gilmour was already adding up numbers how this would hit his local power base and, more importantly, the ‘high headjuns’ down in Glasgow and London. He was a back room muscleman, a conniver from the old school. He was party politics.

And in walked Grindley

Ultimately Cllr Gilmour and the councillors had enough of the bad coverage over the cheap mortgages. Political lives were at stake. Local authority careers in jeopardy. The council decided to ‘move forward’. They really had no choice. They had their backs against a wall. They held a press conference.

And that’s when David Grindley appeared.

He was the hard man from the tabloid Daily Record and didn’t have much time for local authority nonsense. It was the first time I’d ever seen him at the boring old council HQ. A double murder, runaway brides, brawling football stars and more double murders were his trade. Not poxy councils. It was time to show his cards. With dyed red hair, checked suit, handrolled cherry flavoured cigarettes and a bum leg, he dominated a room. His baritone could freeze a pint of Tennants on a hot day. The councillors prattled on about looking forward. Joe Gilmour sat sullen and let underlings do the talking. Tommy Crainie and Colin Liddell scribbled incessantly. Grindley blew sickly sweet smoke in the air, waited his turn and then summarily interrupted the prattle and pointed a perfect roll-me-up at the council bosses, all of them including Cllr Gilmour. ‘The kid gloves are aff.’ Grindley said. ‘We’re no’ here tae listen to your nonsense nae mair.’

‘We tell youse what we write aboot.’ he announced. ‘No the other way ‘round’.

Despite my tin ear for Scots dialect, I fully understood where Grindley was coming from. The reporters would cover, and not cover, what stories they decided on. Grindley, with his fluorescent red hair, his slim tight lips and his deep barrelhouse voice, was right. He came to straighten things out and lay the rules down. Media academics, smooth talking commentators, post graduate students of communications could chatter and publish and pontificate and yaddy-yaddy all they wished about ethics and norms and the balance of the press. But Grindley’s hardcrusted warning put them all in the shade.

“I’m no for havin’ it” he said as he checked his new fangled digital watch (‘Made in America, from Lubbock, Texas’ he once confided to me) and left, no doubt to cover another juicy double murder complete with crying grannies, brawling footballers, a runaway bride or two. All in fourteen tight paragraphs. No fat. All lean meat. Tight as tightness can get.

Anyway, back to the ‘Tizer where I slapped story after story into the paper from the dry bones of council meetings. I would try to keep awake in the suffocating vapidity of the meetings. Usually, after my fellow local reporters had left the chambers, I would talk to those left behind – councillors having a smoke, pallid officials having a smoke, shifty press officers having a smoke. Even thuggish Joe Gilmour having a smoke. Everyone having a smoke. Even me having a smoke.

And then, I’d lope back to The Advertiser and ask myself, just how would Grindley write the tale in lean prose. Tight prose.

Rifling a cross on a pick option….

I was slowly learning. But there were still rough edges, steep curves, deep holes to deal with. One was sport coverage. Everyone had to do it. It was obligatory as it earned ‘lineage,’ which meant all income from selling on the results were slapped in a pool and doled out equally.

Most of the work centred around filing copy about Alloa Athletic, a team which usually bumped along near the bottom of one of the lesser divisions where we knocked heads with Stenhousemuir, Albion Rovers and Raith Rovers. Growing up outside Britain, I had no idea about Alloa Athletic. Nor Rangers, Celtic nor Arsenal. Or about football, for that matter.

But I had to cover it – and, shockingly, had to file for the papers. I defaulted to basketball lingo to get by, giving heart attacks to copy-takers as I described how McNulty “rifled a cross on a pick option” “spread the field when the rimshot failed” or “slammed a rocket while behind the arc”. I still remember one recipient at the Glasgow Evening Times ripping his headphones away and saying to his pal: ”I got a right fucking case here, Alec, a right wee bampot.” But he still took the half time report word for word. And it went in verbatim too.

In the press box, which stood on top of a rickety stand at Alloa’s Recreation Park, I watched as real football reporters plied their trade. They would slide a tiny notebook from a side pocket, sigh deeply as they wondered why they weren’t covering a Celtic match instead of this nowhere snoozefest and write a fragmentary note: “McMinn, Alloa, bad knee…”, “Dodds, slow on the right,” then produce 350 words of flawless copy about the goalless clash versus Clydebank or a drubbing at the hands of Cowdenbeath.

Slowly and painfully, I learned how to dip into the ragbag of tired but faultless footie clicheland: “McClennan rattled the bar. But 90 seconds later Rogers made no mistake from five yards out during the goal line scramble, McFee proving useful in defence…”. I don’t think I ever filed a match without adding that inevitable ‘goal line scramble’. It was my go-to phrase to add colour to a report even I barely understood.

It was here in The Recs, by the way, that I witnessed one of the most whacko match moments ever. The Alloa goalie booted the ball downfield, it ricocheted off a stone and careened high over the heads of the opposing defence and into the net. Go-laaaa!!!!! 1-0. The sparse Recs crowd went nuts, all two dozen of ‘em. And their dogs howled gleefully into the foggy Clackmannanshire night until the final whistle.

As for the reporters in the ramshackle press box, they fell off their barstools into a heap of hackdom. “Well,” I asked. “What do we do with that one?” Shouldn’t have asked. Out came the tiny notebooks- “McConnachie and his bouncing ball..” and “Alloa hits the rocks – and win”.

Meanwhile, the torrent of local stories passed my desk, prodding me to quicken my pace and polish for what passed for style: “Row Over Dollar Glen Safety,” “Big Row over Mar Tower Plan,” “Even Bigger Row Over Brewery Closure” and “Biggest Row Ever Over Hillfoots Road Dangers” Plus one of my all-time favourites: “Bay City Rollers to Move to Dollar.” (they didn’t).

The last doorknock

The Advertiser knocked the rough edges off us all. Many of my colleagues did well. John Knox became a trusted BBC voice covering the Scottish Assembly; Jennifer Cunningham evolved into a dab hand for the Glasgow Herald; Anna Soubry landed as a Tory cabinet minister; Alison Tod worked for the World Service; and Arthur MacDonald went to The Scotsman business desk. The hard working Gordon Gillies, the uber news ferret of Clackmannanshire, became a press officer for the gas board.

So, after a quick tour of duty at The Advertiser, where I learned so much, I found myself at the front door of the Hansen home, a last doorknock, one of my final stories for the paper.

I returned to the newsroom, wrote the piece, a brisk Grindleyesque work of art, and handed in my notice. Another job loomed.

Mr Hardy aimed a long crooked Dickensian finger in the air and reminded me I was imprisoned under an antediluvian contract called indentures. It summoned up medieval images of a shackled man lifting logs for seven years before being allowed to eat with a fork. It meant I had to serve two and a half years as a trainee. I told him I was leaving. And I left.

Then it was down the road, away from Alloa, away from Sheriff Henderson and his short sharp lessons, away from gentle Mr Sweet, away from squabbling councillors, away from the suave Mr Reid, away from Cllr Gilmour and his white loafers, away from The Recs, David Grindley, Clackmannanshire and the ‘Tizer. I was ready to follow a muddy ribbon of possibilities, lined with potholes and dreams and, might I say with an dash of pride, alot of great newspaper and tv stories. Well, one or two… maybe.

**sections of this article appeared in earlier editions

Will Travel

Didn’t know Anna Soubry was a colleague of yours…..

Matthew

What was Hansen’s ungallant behaviour?

Russell Hall

Just read the slow rise to mediocrity (the title for an autobiography if ever I saw one !!)

loved the images of the news room characters. The expression “his baritone could freeze a pint of Tennants on a hot day” is journalistic genius 👍

Tony Fitzpatrick

I could smell the Players No 6….

Ginnie R

Excellent!!

Bella Houston

How about the stuff you didn’t print. Send on the outtakes…

Alan Holland

There’s no finer way to gain experience nor ambition to rise than by starting at the bottom.

What a great beginning. It’s clear from the detail of this piece and the obvious affection in which you hold these early colleagues that you had a wonderful start. Small wonder Mr. Hardy wanted to retain a young man with burgeoning talent, but his work was done. Another fully fledged journalist was leaving the ‘Tizer nest.

Loved it.

Alyson Birch

Mad as a haggis in a jam jar !!!!!

Mark Leder

Love those old days

Nick Dent

Kept tight all the way through

Jane Norris

Brings back old days

Bob Berg

Too short…more plse

Stewart Donaldson

I can across this quite by accident, and it’s an excellent piece. your description of David Grindley whom I knew quite well was spot on. He would have gatherings at his flat in Barton Street, thick with cigarette smoke and put the world to right, or try to!

I met him years later in a restaurant in Malta many years later, and he continued a conversation we had years before. A wonderful chap.

Subscribe to new posts.